Welcome to ConFurence 4! After 5 years we do seem to be getting the hang of it… Once again, we will be doing all of the things that have made our convention a very special event.

This year our guests indudes verry popular author, Mercedes Lackey; illustrator (and now co-author) Larry Dixon; and Ken Fletcher, one of the “founding fathers” of Furrydom.

ConFurence 4 has a wonderful new home too, the Red Lion Orange County Airport. The Red Lion chain has a great reputation with Fandom in general, and I thinkyou will agree that it is a fine facility. The staffhas been incredibly helpful, and we are planning to be back next year! (and next year… and…)

In this little introduction, I like to remind all of our members that this is YOUR convention. Our loyal members have returned, year after year; and spread the word, which is still the very best kind of publicity! Thesponsors and Super-sponsors have allowed us to invite not only important guests, but assist others members who needed a “boost” to be able to attend. You who have stayed in the hotel to be “close to the action”, have given us valuable bargaining power, allowing us to “move up” to a better facility.

Once again, Rodney and myself, and the committee would like to thank all of you for your continued support. Please take some time to look around the Red Lion, enjoy the programming and, most of all enjoy the company of our growing furry family. It is because of you that we do this… that we CAN do this!

This year’s ConFurence is dedicated in loving memory to:

Charles “Deal” Whitley

1956—1992

ConFurence Credits

Co-Directors, Programming, Facilities, Publications: Mark Merlino, Rod O’Riley, John Alan Stanley

Hotel Facilities: Red Lion Hotel Orange County Airport, Costa Mesa, CA. Christina Kellenberger, Convention Services Manager.

Art Show:

John Alan Stanley, Larry Adams, Vicky Levitin

Video Programming:

James Lomax, Henry Brown Jr.

Official Mascots:

Sydney Fisher, Cairn Fisher

T-Shirts:

Terrie Smith, Ken Bolland

Printing:

A E Press, Concord, CA

Committee Members:

Larry Adams, David Bliss, Henry Brown Jr., Farix, Darren Hanson, Brian Henderson, Jazmyn, Chris Keys, Vicky Levitin, James Lomax, Mark Merlino, Kurt Miller, Ken Neilsen, Rod O’Riley, Shayn Raney, Leon Self, Kay Shapero, John Stanley, Joelle Vara, Wolf

Super Sponsors!

John Cawley, Rob Clark, Mick Collins, David Ewell, Allen Fishbeck, Pete Glaskowsky, Jason Jensen, Ron Johnson, Scott Malcomson, Sean Malloy, Anon E. Moose, Paul Ripley, Jerry Shaw, Richard Williams

Sponsors:

Hilary Ayer, Tom Bates, Alan Coe, Jim Drew, Brian Dysart, David Fageol, Richard Falkner, Don Fitch, Tim Fitelson, Steve Gattuso, William Green, Jonathan Hammar, Arlene Harris, Christopher Hutzel, Tracy Kazaleh, Jo Kellner, Robert King, David Langley, Jeff Mancebo, Cat von Otter, Valerio Pastore, Dar Ned Soltice, Jim Trimble

The Quest for the

Oldest Furries

by Fred Patten

Three years ago, I wrote aguest editorial for a funny-animal theme issue of Edd Vick’s FANTOONS (#33), in which I postulated that the 1990s were the centenary of the first funny animals. Anything earlier than that “did not count”. Since the theme of ConFurence 4 is “In Search of Ancient Furries”, I have been asked toexplain this theory, andsee if I can’t find some funny animals before the 1890s, after all.

In FANTOONS #33, I had said, “ Why say that funny animals go hack for only a century? What about the talking animals in Aesop sfables, or the anthropomorphized court of King Lion in the medieval romance of Reynard the Fox? Anthropomorphized animals certainly existed in folk tales, literature, and satire back to before recorded history. But these were not irtdividuab as much as they were abstractions. Reynardwasnotjustafox, hewas the epitome of all foxes. Similarly, Brer Rabbit and his neighbors in West African folk tales were thepersonifications of their species. Coyote the Trickster was the divine Troublemaker. Puss in Boots and the Little Humpbacked Horse were not so much animab who could talk as they were fairy godmothers or benign nature spirits helping someone who was pure of heart. Little Red Riding Hood’s wolf was a metaphor for worldly dangers that await the careless. Even Thomas Nast’s Democratic donkey and Republican elephant were not the funny-animal charac¬ ters that they have become under 20th-century political cartoonists; they were more remote abstract symbob. Funny animab as individual characters, with personalities of their own, did not really exist more than a hundred years ago.”

Some people have traced the first anthropomorphized animals back to the prehistoric cave paintings ofover 10,000years ago. The problem with that is that it is not really certain what those paintings are supposed to represent. They could be animals walking upright, or animal-headed gods. But they could also be depictions of tribal priests wearing animal masks or headdresses.

Ancient religions were certainly full of gods and spirits that mixed human and animal attributes. Animal-headed gods such as Bastet and Anubis of the Egyptians, or Ganesha and Hanuman of the Hindus, are well-known. Contrariwise, the Assyrians and Babylonians showed their supernatural neighbors as having hu¬ man heads on the bodies of winged bulls or lions. In Celtic mythology, phoukas or pookas were malevolent spirits that took the form of some animal, always black and often a horse, to lure an unwary person to a horrifying doom. The Japanese counter¬ parts of these were the badgers and foxes, who would take on human guise to play malicious pranks.

But there are also humorous Egyptian drawings from around 1500 B.C. that show common animals walking on their hind legs and engaging in normal human activities. A donkey and a lion sit at a table, playing chess. A cat, with a farmer’s knapsack slung over his back, herds a flock of geese. These do not have any supernatural significance; they seem to be solely for amusement. These could be called the oldest funny-animal drawings. But that’s all that they are— funny drawings. No attempt was made to give the characters any real lives or personalities, unlike the gods and demons who often had elaborate mythological biographies built up around them.

Aesop’s fables are another example of Ancient Furries. Aesop’s life is traditionally given as from ca. 620 B.C. to 560 B.C. Many of his fables feature talking animals who are more than just personifications of their species. The congress ofmice who debate over which of them should bell the cat—the frog who puffs himself up to show the other frogs how important he is—the fearless mouse who frees the proud lion from the hunter’s net. These are astart at giving animals individual human personalities. But the characters are not really individuals as much as they are abstractions. Their primary purpose is to dramatize the edifying moral of their fable. In my opinion, they are not yet genuine fun ny animals.

A Japanese parallel to the Egyptian drawings is the Animal Scrolls of the Buddhist priest, Toba (1053-1140 A.D.). These show frogs, foxes, monkeys, and other Oriental animals busy at the same human activities as the Egyptian animals drawn 2,500 years earlier. The major difference is that the Egyptian animals were usually naturally nude, whileTobadrew his animals dressed like priests, noblemen, and wealthy merchants. But again, these are j ust am using cartoons. None of the animals have any individu¬ ality or personality.

Most of the medieval European talcs which feature talking animals depict them as either species-personifications (the sly fox, the loyal dog, the gruffbear), or as magical saviors of the innocen t. Some scholars claim that stories such as Puss in Boots (which is centuries older than the now-standard literary version by Charles Perrault) are deaned-up modernizations of pre-Christian legends, with the benevolent forest spirits revised into cute nurserytale characters to avoid condemnation by the Church for paganism. But there are a few exceptions in which the animals seem too common to be gods, and are well-enough characterized to be more than just species-abstractions. The Bremen town Musicians are an old dog, a cat, a rooster, and a donkey (in some versions a goat) who realize that they have grown too feeble to carry their own weight on their farm any more, and escape together before the farmer decides to kill them as useless. They find a hut in the forest that is the hideout of a band of robbers, and they frighten the robbers off so they can claim the hut as their new home. There’s no magic or nobility here; just common sense and self-preservation. The Bremen Four are awfully close to funny animals. Unfortunately, there is no individuality among them, any more than there is in the pre-Disney seven dwarfs.

Okay, here’s a live one! Sun Wu-K’ung, the Monkey King. The legend of the Stone Monkey grew in folk tales for about 500 years before it was novelized as The Pilgrimage to the Westky Wu Ch’eng-En (1506?-1582?). Wu’s hundred-chapter novel estab¬ lishes Monkey as a flamboyantly individual character, loaded with sarcastic wit, pride, and also bravery and loyalty. Monkey’s sidekick, Pigsy, is also clearly a separate character with his own personality. But The Pilgrimage to the West was not known in the West for another three hundred years, and so it did not influence the evolution of funny animals.

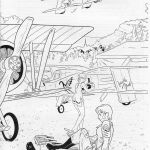

Lewis Carroll’s original illustration of Alice, the Gryphon, and the Mock Turtle. (From Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, the hand-written & -drawn version of the story given as a Christmas present by Carroll to young Alice Liddell in December 1364.)

I hadsaidin FANTOONS that funny animals as we know them today only go back to the 1890s. I’ll concede that a good case can be made to stretch that date a further thirty years back, to the 1865 publication of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Won¬ derland. That extremely popular novel featured many talking, clothes-wearing animals, starting with the White Rabbit with his waistcoat and watch. The Dodo, the Cheshire Cat, Bill the lizard handyman, the March Hare, the Gryphon and the MockTurtle— most of them had very brief roles and no personal names, but each was obviously a genuine individual rather than a spedes-stereo- type or a fairy in animal guise.

Scholarly opinions differ as to whether Carroll instantly inspired lots and lots of imitators, or whether it was “funny animal time” and the various Victorian-cra authors of juvenile literature all independently began using talking-animal characters around this time. Jean Ingelow’s Mopsa the Fairy (1869) brought her little-boy protagonist, Jack, to Fairyland by having him fly there on the back of a giant, talking albatross. The inhabitants of Fairyland

included numerous talking animals, including the ghosts of horses who had been beaten to death by brutal human masters. Carroll and Ingelow set their stories in what were transparendy children’s dreamlands, but Carlo Collodi’s 1880 The Adventures of Pinocchio was supposedly set in the real world. The living puppet was admittedly “unusual”, but the moralistic talking cricket and the anthropomorphic evil fox and cat were presumably “normal” characters. Also in 1880, Joel Chandler Harris codified the African animal fables of the Afro-American culture into a literary Southern Black funny-animal community. In Chandler’s Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings, and its sequels such as Nights With Uncle Remus (1883), he showed how“Uncle Remus” had taken the abstract animal characters of the original fables and turned them into distinct individuals with colorful personalities.

So maybe funny animals did begin before the 1890s. During that decade they became downright common. Jimmy Swinnerton created the first newspaper anthropomorphic cartoon characters, with his Little Bears in the San Francisco Examiner in 1891. Most anthropomorphic characters up to this time were at least slightly humorous; the first completely dramatic ‘morphs appeared in Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Booh in 1894. Kenneth Grahame’s veddy-proper Reluctant Dragon showed up in 1898, ushering in a fad for fabulous monsters who displayed formal English etiquette, as with the top-hatted Archaeopteryx,

the umbrella-carrying Dodo, and the merry-go-round-riding Palacotherium in G. E. Farrow’s The Little Panjandrum’s Dodo (1899). Talking animals on the other side of the world presented a more serious dramatization of ecology and natural history in Ethel Policy’s Dot and the Kangaroo (1899), possibly the first appearance of Australian ‘morphs. Yes, by the 1890s funny animals had become well-established as “real” fantasy characters, not j tust allegories or disguised nature spi ritsor figments ofa child’s dreams.

Introducing the animal kingdom’s first superstar:

Reynard the Fox

by John [the fox] Cawley

The History of Reynard the Fox

Told since the beginning of tales, Reynard the fox and his adventures were handed down verbally for centuries, finally appearing in writingin the twelfth century. The storiesof Reynard take place in a medieval kingdom ruled and mostly inhabited by animals, though humans also appear.

Originally aseries ofshort tales, the epic was fashioned into its most famous form by Johann Wolfgang Goethe in 1794 at the request of a friend who felt the Germanic based tales were that nation’s “Odyssey”. A darkly comic piece, Reynard’s personality and adventures are unique amongst almost all the great characters of literature. He is presented as despicable and a wily survivor at all costs.

Not alone, the supporting characters are also depicted as evil, vain, stupid or merely uncaring. There are large doses of violence, death, deceit, treachery and rape. The tale’s moral, “cleverness and deceit will always triumph,” are of dubious value.

Reynard, illustrated by Laura Bannon. as he appeared in Andre Norton’s Rogue Reynard (1947).

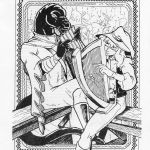

King Lion and Reynard by an uncredited artist in a 1884 children’s version (told with words of only one syllable).

Reynard the Fox – His Tale

Reynard, formerly a high ranking member of the king’s court, has hit upon hard times. His many enemies and victims try to incite the wrath of the King via charges against the fox. This villainous vulpine’s enemies include the powerful Isegrim (wolf), Tybalt (cat) and Bruin (bear). On thesideofthe fox are Greybeard (badger), Dame Ruckenaw (monkey) and Ermelyne (Reynard’s wife). Trying to sort matters out are King Noble (lion) and his Queen (lioness).

His enemies have strength and numbers; but Reynard has his wits and his lies. The fox manages to sidestep one charge after another, always fooling the King and Queen with his talcs. Finally Isegrim initiates a physical battle that will settle the disputes once and for all.

Reynard and Martin (an ape of the cloth) drawn by W. Frank Calderon in the late 1800’s and used in numerous editions of the story.

Reynard becomes Superstar

Reynard’s ascension to superstar status didn’t occur until the middle 1800s when an exhibit from Germany appeared in England. Part of that display were elements of the story (mounted animals in clothing). So intrigued and Reynard-happy did the populace become that Charles Dickens wrote up a special sum¬ mary of the story for a major magazine.

For the next hundred years Reynard’s tale popped up in numerous books aimed at children and adults. Even noted science

fiction author Andre Norton offered Rogue Reynard’m 1947. The Disney studio labored over three decades trying to bring the fox

to animation. Walt finally gave up, conceding that Reynard was too much of a villain to be the hero of a Disney movie.

As gentler animal tales became more in vogue, Reynard’s violent adventures were no longer considered suitable for young readers. Though some writers tried to clean up the tales, most, like Disney, found this villainous vulpine too cruel to be the center of any socially conscious story.

For almost halfa century he’s been hiding. But hiding is not Reynard’s style. He’s ready to come back. The world has caught up with him and his vicious ways. Reynard’s claim of” Self-interest will always be in vogue,” makes him a fox for the Nineties.

Adapted from John Cawley’s comic proposal, “Reynard the Fox: The Villainous Vulpine” (© 1991 John Cawley).

John Cawley has been intrigued in foxes si nee a youngage and has been seriously collecting books and artwork on foxes since the early Seventies. He is a professional in the animation industry and author. His screen credits include Associate Producer on GARFIELD AND FRIENDS as well as BOBBY’S WORLD, and (the original) AN AMERICAN TAIL As an author and publisher, he is responsible for such volumes as The Animated Films of Don Blnth, The Encydopetlut of Cartoon Superstars, and Cartoon Confitlenliut

Reynard resting, illustrated by J. J. Mora in a 1901 U.S. translation of Goethe’s poem.

Aristheron felt another succubus drift and flutter down to her level in the coils of Hell’s comfortable, viscous ether. Stilling the thoughtful swaying of her own wings, she let herself feel the disturbance of the other succubus. The ether parted around a foxlike body, like her own, around silken raiments, and small ornaments upon the ears and the left breast. It was her sister, Aristrides, and she had her compact disc player with her.

Aristheron’s tail quivered with her delight at seeing her numerical sister, heryoungersister. They slipped intoeach other’s arms, four pairs of them entwining, and became reacquainted with each other’s bodies, which were, to the sight, identical.

“Hello, sister,” purred Aristrides, having settled after the intimacy into her usual flippance. “How are you this evening?” Aristheron heard her click on the player, heard the chuffing of the rotation of the disc inside, and then heard something’s out of the headphones.

Aristheron flitched her ears. “What is that—well, I hesitate to call it music—?”

Aristrides grinned, waving her tail. “It’s called ‘rave.’” “It sounds like a great turbine with a beating heart.”

Aristrides smiled at her sister. “ That was as unintentionally astute a description of it as any I’ve ever heard.”

Aristhemn wrinkled her nose. “It is not as dissonant as ‘grunge.’ But is it not a little… extreme?”

The other succubus smiled. “My dear sister, your idea of daring is the later works of Mozart.”

Aristheron shivered a little with delight at the thought of a well-turned piece by Amadeus, and then looked up, wondering if she ought to look as though she’d been caught at something naughty. Out of habit she did so, because she looked very attractive doing it, and had for the last four thousand years she’d been using the trick.

“What is wrong with Mozart?” said Aristheron. “1 happen to like music with dignity, and why not? I am your elder sister…” she said warningly.

“You’re elder to me by a millisecond,” said Aristrides with a grin. “You’re just afraid of change, is what it is, Aris. Like with your body.”

Aristheron rattled her wings together. “I do not wish to be pierced,” she insisted, looking at her feet. “I have no desire to mar the body my master gave me.”

Aristrides smirked. “You’re just too proud of yourself. As well you should be,” she murmured. She unashamedly cradled her sister’s breast; Aristheron smiled back at her equally shamelessly, and purred a little in her throat.

Aristheron blinked her deep black eyes cutely and whispered “Why should I not be especially fond of the m usic that my lover wrote to please me?” in the gentlest voice she could manage.

Aristrides’ jaw dropped. Before long the sweet, tinkling laughter of the two succubi flittered through the ether of Hell.

—William Haas

A Modern Totem

By Mark “sylys” Merlino

One of the origins of what we call Furry is the spiritual concept that is common in much Native American and other elder cultures, that of Totem Animals. The Totem Animal is a personalspirit, aprotector, aguide, much like the Guardian Angel of the Christian ideology.

In the varied mythos of the Native Americans, individuals would locate theirT otem Animal in different ways. Some believed it was a birthright, much like a baptism. The first animal the new born perceived would be that child’s guardian for life. In other tribes, finding ones guiding spirit was a rite of passage into adulthood. The individual would go on a “Vision Quest”, a lone journey where exploration of self was the true goal. Once found, the person’s Totem became a constant companion, an older and wiser “soul brother orsister”, someone to learn from and emulate. Native Americans believed the animals were the original people with the knowledge of how to live a correct life, in balance. Man was but a child, with a great deal to learn.

As the knowledge of modern man increases, we find that it is not how much we know, but how much we need to understand. Our perceived progress has become less attractive. In many cases, it is the animals we love who have been the first victims. They show us our mistakes too often by the sacrifice of their lives. Once again, Man learns from the animals the most important lessons… hopefully not too late.

The major difference in these modern lessons and the ones the Native Americans shared with their animal kin was that for them, it was far more personal. There is no modern example of such individual bonding with our animal kin… except, perhaps for the selection of animal persona, as is common in Furry fandom.

The animal that we choose to be ours… to be US in many cases, it usually one that we feel some attraction or kinship too. Animals seem to us to lead a simpler, more direct life. They have less “hang-ups”, are more aggressive and tend to go after what they want. We are stifled by our own society, which teaches us that what we feel or imagine is wrong. Our animal sisters and brothers teach us that we have little to fear, and nothing to be ashamed of.

There seems to be a basic human need; to have an advisor, a teacher, to show us the way. Even after we graduate from educational institutions, and have those papers that say we are complete and ready to live in this world… we still seek guidance. Organized religion in many ways is too impersonal to satisfy our desire for the “elder brother” at our side. It is possible that our native American ancestors had the right idea all along, and that we just became distracted for a time by our “advancements”.

We look longingly at our wise and beautiful animal brothers and sisters, and wish we could be one with them. The animal we choose as ours; to be our personal representative, our other self, just may be a Modem Totem.

How to Give a King a Really

Hard Time

by Rod O’Riley

The world of legend abounds with tales of ancient animal gods, many of great power and renown. Usually these tales and the animal people in them reflected the surroundings and times in which thestories arose, and quite a bit of the culture that gave birth to them. This leads to an amazing diversity of stories and myths throughout the world. Yet, one can find at least one creature, one aspect of mythology and world-view, that makes its appearance in an amazing number of cultures, in different forms, yet with striking similarides. This creature is The Trickster.

The Trickster is, among many other things, a complex character. It is usually described in stories as vain, loud, rude, and ageneral pain to be around, yet thestories concerning it are usually among the most beloved by the listener—in other words, this is a hero. The Trickster is inevitably, unshakably greedy, for food {often for food!), wealth, sex, respect, you name it; yet its very struggles for things that most of us wouldn’t mind having give it a sort of pained dignity in our eyes. It is clever, and a lover of practical jokes and trouble-making, but it is also exceedingly foolish, and often likely to get caught by its own schemes. The Trickster is the one the ruling creator gods don’t like—often because it messes up the world by pulling silly stunts like creating the sun, or fire, or people, etc. In short, The Trickster is the comedian of folklore—though its various manifestations would like the thought of anyone laughing at them. And I believe that in its own way, The Trickster has a very important function: It is change, and the eternal struggle against authority. Let me introduce you to two very popular animals of folklore who are avatars of The Trickster: Coyote and Monkey.

Throughout Native American folklore of many cultures, about the most popular and common character is Old Coyote. (To northern tribes it may have been Crow, or in the south it may have been Fox, but trust me, it’s the same character.) Coyote was a magnificent critter—sheer appetite and vanity embodied in fur. In some stories, he functions purely as a clown: trying for a meal, or to prove his own worth, or to steal an object of value, and winding up with nothing but a sore body and a bruised ego. Yet,

Illustration from

Fur Magic by

Andre Norton.

Coyote would bounce back, ready to try the next scheme and take the next failure. (The comparisons to Chuck Jones’ Wile E. Coyote are obvious, though Mr. Jones claims in his autobiography Chuck Amuck to have been more influenced by the works of Mark Twain.) More importantly, this was a creature of magic, who would readily use his powers to further himself and his goals, to get back at someone, or simply to play a mean trick on an unsuspecting person or god. These very powers and andcs often made Coyote an important part of creation myths—he was not the creator, not the ruler of creation, but the changer of it. This makes him sort of a devil character in Andre Norton’s Fur Magic —Coyote is the one who “turned the world over” and changed it from the rather placid order set up by the less frantic creator gods. Yet, by this very act, Coyote gave us the world we now live in—including the humans in it. Coyote has an impor¬ tant funedon in a great many stories involving the creation of humankind—he was the makerofall the tribes. So, it would seem that humanity owes a debt to this troublemaker god, even as we might snicker at his antics.

Over across the waters in the cultures of the orient, we find Monkey, also known as Cioku or The Monkey King. This fellow is more clearly a hero, being thought of as more clever and generally kind-hearted than Old Coyote. Yet still, Monkey’s primary goals seemed to be getting food, bettering himself, and stroking his own ego; and these tended to get him in all sorts of trouble. Monkey travels to Heaven to find better standing for himself and his people, yet he gets on the bad side of the Emperor of the Gods (or in some stories, Ruddha) for general mischief. So the gods conspire to destroy him—and fail. Then they send him on impossible quests, certain to bring him failure and death—and he succeeds, often if only by sheer Attitude. Through it all, Monkey acquires more and more magical powers, and uses them to make the world more to his liking. The gods consider Monkey a rude, foolish, annoying creature, yet everything they try to do against him makes him look like a hero and makes them look foolish! In his way. Monkey’s adventures with the gods reflect an often overlooked aspect of oriental culture—making nasty, often hilarious fun of your rulers behind their backs, even as you cower before them.

So, we have two furry critters in two distinct cultures, whose primary functions seem to be representing many of the worst aspects of people, getting on the nerves of the gods, and along the way by perhaps pure accident, twisting the world around to look something like it does today. And of course, fulfilling the primary function of comedians—giving the people a good laugh at themselves and their lives, and maybe more importantly, a ray of hope that life’s struggles may actually come to something good.

Background:

Two books recommended for stories of Old Coyote and Monkey King, respectively, are Giving Birth to Thunder, Sleeping with his Daughter by Barry Lopez, and Dear Monkey by Arthur Waley. The title of this piece was handily lifted from George Carlin.

Rod O’Riley works as an environmental engineer in Southern California. He is Co-Director of ConFurence.

cover every situation—when an artist can be approached, whether he expects to be paid, and what sort of drawing may be asked for.

In the wake of ConFurence, other conventions have be¬ come unofficial furry cons. Places where significant numbers of furries will collect and party include the annual Worldcon, the San Diego Comics Con, and lately Philcon. Other completely furry cons like Confurence have been talked about, but not yet held. It’s probably only a matter of time before somewhere in Canadaor the U.S., someone announces a Confurmation or Furmentation or something of similar name.

The one area of the funny animal field that once led and perhaps lags now, is the black and white comic. Outside of the mainstream comics industry, there has been a thriving b/w field; a direct descendent of the undergrounds but no longer counter- cultural. Various politically-correct, nihilistic, erotic, barbarian, artsy-fartsy, samurai, japanimation, and superhero comics con¬ tend with each other for sales in a limited market… among them furry comics.

1984 was a good year for furries. The best known and earliest furry comic was “Omaha the Cat Dancer”, created and drawn by the same Reed Waller who once co-edited Vootie. Omaha began in Vootie in fact.Theearlieststories to be published outside the apa appeared in Bizarre Sex comics, in 1982, then under their own title in ’84. In the same year, the first of Joshua Quagmire’s five issues of “Cutey Bunny” entered the scene. Also, the first proper issue ofSteve Gallacci’s “Albedo”, and possibly Jim Groat’s “Equine the Uncivilized’’. 3

The next landmarks of b/w furry comics that appeared in years after, included William Van Horn’s “Nervous Rex” (1985), Stan Sakai’s “Usagi Yojimbo” (1986), “Captain Jack” by Mike Kazaleh (1986), and the focal point comic published by Fantagraphics, “Critters” (1986). Critters published almost everyone at one time or another, and did the unheard-of for a long time—it appeared on a bimonthly schedule. Unfortunately, the better contributors drifted slowly out, and were replaced by less popular artists. By the fiftieth issue in 1990, “Critters” had lost its commanding place and was cancelled.

For a brief while there was some hope that Eclipse’s gemlike “ Dreamery” might take up where the declining quality of the Fantagraphics book left ofF. But its 14 issue life only lasted from ’86 to ’89, dying a year younger than “Critters”. The one great service done by “Dreamery”, fortunately, was introducing Donna Barr to the public. Soon afterthe last issue of“Dreamery”, the first issue of “Stinz” was on the shelves of comic stores.

The next big event in the evolution of the furry comic was the five-part mini-series by Vicky Wyman, Xanadu, followed by a single colour special. After wrapping up the series, the story moved ominously downscale—to a fanzine. Lex Nakashima’s “Ever-Changing Palace” was a lavish production, but a fanzine nonetheless. What did it mean when superior material reverted to the level of fanac?

Possibly it meant nothing at all. But, if it meant the field was not viable, certain people were unwilling to admit it—luckily. Martin Wagner launched his popular Hepcats series in 1989- That same year Edd Vick established MU Press.

MU’s fledgling production was a small paperback collection of Steve Willis’ “Morty the Dog” stories. In rapid order Edd

added new titles to his line. Over the years MU has published several fine, and several puzzling, titles—’’Rhudiprrt, Prince of Fur”, “Mad Raccoons”, “Champion of Katara”, “Furkindred”, “.357”, “Zu”, “Wild Kingdom”, “Beauty of the Beasts”, “Shanda the Panda”, and many more. In spite of disappointing sales and irregular releases, MU is perhaps still the best hope of legitimizing furry comics.

Much more recently, Antarctic Press has entered the contest, with a new series of “Albedo”, and the pro-military “Furrlough”. In this case, twoover-heads are definitely better than one. Two companies hopefully have better than twice the op¬ portunity to wedge an entry into a tight market.

But by and large the furry comic field hasn’t grown since its beginnings in 1984. Many titles have come and gone. About as many are published now as were published eight or nine years ago—some five, arguably six, titles, apart from the sporadic MU stable. Sales are insignificant for all but two, “Omaha” and “Usagi Yojimbo”. The rest, (limping along with sales of three thousand, two thousand, or far fewer), might almost be called glorified fanzines.

In my view, this is the single greatest obstacle to the creative growth of furry fandom. It grows in numbers, but not in dimension. Fan artists increase, as does the fan press. But the professional side of the field is perpetually on the verge of breakthrough, without quite breaking through.

Where are we going as a social phenomenon? The question has been asked again and again, and the answer each time likely says more about the individual than it does about the future of furry fandom. There does seem to be a ground swell of interest in the furry motif. Itshows itself in growing numbers and increasing cross-links in the electronic media. Confurence itself grows, if slowly. But is this growth from a static body of potential furries? Or is the furry sensibility spreading? Can it grow far without more developmentofits public face, the comicbook? Or is a professional side in fact irrelevant? These questions will only be answered in time. My guesses are no better than yours.

1 An apa (Amateur Publishing Association) is run on a contributory basis. Each member is required to produce and send in to the Official Editor his quota of pages. TheOEbundles these together as identical mailing that are sent back to the members.

3 Also “furverts”, and on occasion “skunk fuckers”.

3 Not formally dated, the attwork seems to have been drawn in 84.

Larry Dixon

Artist LARRY DIXON hails from Tulsa, Oklahoma. His handiwork can be seen in publications from TOR Rooks, DAW Books, Baen Books, Bard Games, TriTac Games, and Eclipse Comics. He is one of the conceptual designers on the award¬ winning computer game. Wing Commander Two.

He is the interior illustrator for the DAW hardcover “Mage Winds” scries, and for The Black Gryphon. His frontispiece “Fa¬ ther Dragon” is featured in the hardcover The Elvenbane co¬ written by Mercedes Lackey and Andre Norton. He the cover artist for Summoned To Tourney, the sequel to Knight of Ghosts and Shadows co-written by Mercedes Lackey and Ellen Guon. He is turning in the frontispiece art for Piers Anthony’s collaborative book, Through the Ice and designing the promotional art for the Anne McCaffrey “Partnership” collaborative scries. Many con¬ sider him to be one of the finest black-and-white illustrators in the fantasy field today.

His comics work has been featured in four issues of FUSION, including the two-part issue, “The Nestling” written by Christy Marx. He is currently collaborating with Mercedes Lackey on a number of projects, including the SERRAted Edge Series for Baen Books; his book, Bom To Run, was published in March, and he has a high fantasy novel in collaboration with Mercedes, The Black Gryphon, which takes place in the pre-history of Valdemar.

One of his possible projects for the future is as illustrator and co-writer for a young adult novel, Owlflight.

He will also be producing a project portfolio as well as the frontispiece for the Lackey-Norton collaboration, The Elvenbane.

He has a new line of pewter jewelry and miniature sculp¬ tures featuring the family crests from The Elvenbane, the crest of Valdemar, and the Black Gryphon himself. He has a new line of hand-pulled silk-screen T-shirts, including the Black Gryphon. His latest print, The Feathered Serpent, appeared in the September 1990 issue of US At, and a print of The Feathered Serpent is currently hanging in Anne McCaffrey’s living room.

He bases all his work featuring fantasy characters firmly in the real world of anatomy and design—”A dragon won’t model for you,” as he puts it. Strongly interested in the ethics of the sf art field, he is considering putting together an “ethics and practices” booklet for new artists .

He has “adopted” RJ, a Golden Eagle, and an American Bald Eagle, Coacoochee, being cared for at S.O.A.R. (Save Our American Raptors) in Apopka, Florida. He has successfully rehabilitated a kestrel (American Sparrowhawk, the smallest of the North American falcons) in the bathroom attached to his studio, which was released in March of 1991. When work on the studio of their new home, “The Aerie,” is complete, he and Mercedes plan to take on many more rehabilitation projects and acquire their apprenticeship birds for falconry training.

He is also planning many renovations to “The Aerie”— called by Mercedes “the weirdest house in Oklahoma,” a3000-sq- ft poured-concrete dome beneath a 5-story octagonal wooden shell. He plans to build a two-story studio which will incorporate spaces for every form of art from sculpting to computer-aided art, build a series of decks and walkways that will incorporate habitats for wildlife underneath, construct a mews for both their rehab birds and their falconry birds, and create an aviary-hot-tub-room.

In his copious spare time, he is a brain surgeon and test

He and Mercedes Lackey were married in mid-December,

Mercedes Lackey

I began reading sf because my father read it, the books were lying around the house, and the covers looked interesting. The first sf book I ever read was Agent of Vega by James Schmidt; my second, Beast Master by Andre Norton, thus beginning a love affair with Norton’s books that has continued to this day. One of the most exciting things to happen in my career as a writer was to be invited to write a “Witch World” story for the first of her “Friends of Witch World” anthologies; it was literally a dream come true, since back in the dark ages, when I was a Kid, I wrote (handwrote, and illustrated) many Norton pastiche stories when I couldn’t find any new books to read.

I wanted to write professionally—but was perfectly well aware that writers don’t make any money—so I chose instead a career in science, getting my B.Sci. in Biology from Purdue University in 1972.1 then discovered that B.Sci.’s don’t make any money either. As a result I ended up in a variety of jobs, from waitress to security guard to artist’s model. I finally ended up in a job which started out as telephone survey work, and ended up as a “programmer” doing some very simple “ctxikbook pro¬ gramming” for Indiana University at South Bend. From there I went into a computer programming training class for Associates (those wonderful people who wan t to lend you money at exorbi tan t rates of interest); I stayed there for three years, then took a job with American Airlines. In 1990,after eightyears with them, I quit and went full-time as a writer.

In 19901 also married my partner Larry Dixon; in 1991 we moved out ofTulsa into the country, into “the weirdest house in Oklahoma.” This dwelling began life as a concrete dome (single piece, not geodesic); it then acquired an octagonal wooden shell, raising it from 2 1/2 stories tall to 5 l/2stories tall, where it looms over the countryside. We also found ourselves a Master falconer and will be beginning our apprenticeships soon. This means lots of (dead, with feathers, heads, and feet) frozen quail taking up space in the new freezer… It’s wonderful being in the country, where the loudest sound is acow, and ifyou hear ashot being fired, it means someone just potted himself a rabbit or a duck.

When I first began trying to write professionally, I joined the Friends of Darkover, a correspondence fan club for Marion Zimmer Bradley, and asa resultof that and the fact that I had flight benefits, got to know Ms. Bradley personally. She encouraged my attempts, and actually bought my first professional story sale, “A Different Kind Of Courage” for the anthology Free Ama 2 ons of Darkover.

My family background—I’m divorced, (amicably, from Tony Lackey who is still a good friend; we had no children); and I married my partner, artist Larry Dixon, in December of 1990.

I have one brother, Scott, who got married to one of my best friends which I find very convenien t! My father was one of the fi rst commercial computer programmers, so there are a lot of reasons

for me to be in sfi Both my father and mother encouraged me to read anything I could get my hands on, and to think for myself.

I write now because I have to; I couldn’t not write. It’s an addiction; fortunately one that brings money in rather than costing money! I write out of a deep need to tell a story, a good story—one that will touch people the way the books I read touched me. I’m not entirely certain that writers have much of anything in common with each other except for that addiction; certainly all the writers I have met have had personalities as wildly varied as any random group of people. My primary influences are C. J. Cherryh (obviously, since she was my mentor), Marion Bradley (equally obviously), Andre Norton, Theodore Sturgeon, and Anne McCaffrey. I don’t think I’ve written any “major” works as yet—the one I think is best is always the one that isn’t published yet. I try to keep my style simple; the emphasis should be on the story, on the characters, and not on any fancy song and dance act with language. All of my writing starts with the characters—and how they react to the situation I put them in, the problems they face. And they have to face problems; they have to grow and change as a result of those problems, or you don’t have a book, you have a stale intellectual exerdsc, sterile, a dead-end.

But by thesame token, a writer can’tcver come to the point where she feels she can’t learn anything. Every book has to be better than the one before it in some way. The writer has to learn something from the book, and from the problems it poses to her.

I like to write lyrics while I am writing a book; particularly if I seem to have gotten stuck in a particular scene. I find that writing a lyric crystallizes the motivation of the scene for me; having found the motivation, I can go back to thatsceneand make it work properly. CJ tells me that j/;rdraws the scene, or the pivotal moment from that scene, or even a portrait of the main character; she says that does the same thing for her. I also like to create the “folk songs” of the time and place; I find it gives an added feeling of realism to the work, both for myself and for others.

My very first book—which turned into three books!— began with a dream. The dream was quite short; it began with Rolan Choosing Talia, then moved directly to the scene where Talia meets the Queen and accepts the position of Queen’s Own. 1 here was some implied knowledge there—I “knew” something ofthe history of the Heralds, and was told the entirety of the Arrow Code which is used in the third book. All the rest came from asking myself why all this was happening, what the background could have been, and what this youngster would find herself doing now that she was in this position. The “Herald Mage” books developed from a few bits of “history”—and the fact that my editor wanted “magic” in the first chapter of the first book, and there is no real magic in Talia’s time, so I was forced to have Talia do what I used to do—to daydream herself into a time of legend (in my case, the England of Arthur and his knights) as she is reading a book; partially to make the book last longer, partially because she has a very active imagination, partially as escape from her dreary life. From that scrap of the last moments of Vanyel’s life has come an entire set of three books—probably well over 300,000 words.

I am fortunate in having been able to create this world— and it it a world, with a history as long and varied as that of our own. I doubt I am going to run outofideas at any time soon! The real problem is in choosing which story to tell next.

I am equally fortunate in the other world I’ve been able to create—the one for my horror/occult series about investigator Diana Tregarde, which is also the one in which the urban fantasy series I am writing with collaborator Ellen Guon is placed, as well as the one in which the SERRAted Edge series is placed. It’s “our world”—plus. It’s fun—and very much wide open to all sorts of possibilities (including a tentative Di crossover into the collabo¬ ration) because we are literally working with the whole world. Writing with a collaborator is one of the most exciting things I’ve ever done. It’s a lot like writing only the “good parts,” because in a good collaboration, you build on each others’ strengths.

Currently I’m going to be doing more collaborations with other folks. These include The Black Gryphon with Larry Dixon, asequel to Knight of Ghosts andSltadowscaUcd Summoned to Tourney with Ellen Guon; the SERRAted Edge series with Larry Dixon, Mark Shepherd, and Holly Lisle; a “brainship” book The Ship Who Searched’, with Anne McCaffrey; and the “Bard’s Tale” computer-game tie-in books with Jo Sherman, Ru Emerson, and Mark Shepherd. I will be doing two more SERRAted Edge/ Tannim books with Larry, and probably more SERRAted edge books with other folks. I will also be doing a third book with Ellen, Beyond World’s End. I will be collaborating with Marion Zimmer Bradley on the next Darkover books—working right now on Darkover Rediscovery. I will also be working on a collaboration with Piers Anthony, a two-book (so far) series. If I Pay Thee Not In Gold and / Will Pay Thee In Silver.

For solo projects, there will be two more Diana Tregarde books, Triangle Park and Arcanum 101; two Valdemar books, Winds of Change and Winds of Fury, the next rwo Bardic Voices books, The Rohin and the Kestrel and The Eagle and the Nightin¬ gales, ; and a major dark fantasy-mainstream crossover involving Native American mysticism with mystery—kind of Tony Hillerman with magic. It will be called Sacred Ground, and I am very fortunate to have several Native American folk helping me make sure I stay on track with it.

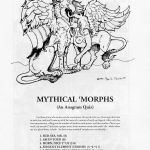

MYTHICAL ‘MORPHS

(An Anagram Quiz)

For those of you who are keen on the uncommon .this puzzle is for you. Rearrange the letters in each clue, and you’ll come up with the name of a creature of myth and legend. After each clue is an enumeration, telling you the number of words in each answer, and the number of letters per word. An asterisk (*) indicates a proper noun. Some answers contain the article ‘the’, while others are in a plural form, or both. See how many mythical ‘morphs you can identify…

1. MID-SEA, MR. (8)

2. AM IN TOUR (8)

3. HORN, NICE V US (3 8)

4. SH! SCOT ELEMENT (HORNS?) (3 *4 *4 7)

5.1 FRIGHTEN; BEAR HOT DANGER (3 4-9 6)

6. EYETH IT (3 4)

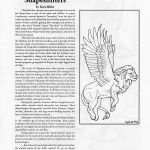

Lycanthropes and Shapeshifters

by Kurt Miller

The belief that a person can assume the shape of an animal has always been a part of our myth and folklore. In pagan Scandanavia, warriors known as “berserkers” wore the skins of wolves and bears in the belief that they would be possessed by the spirits of those animals, gaining their strength and prowess in battle, (the word “berserk” means “bear-shirt” in Old Norse) while many tribal shamans believed that they could send forth their astral forms, which would then materialize in the form of their totem animal.

This belief was shared by many other cultures, including the Eskimos and the American Indians, and is thought to have been the origin of werewolves in medieval folklore. In many cultures, the Gods often travelled in the form of animals. Among the Norse, Freyahad a magical cloakoffeathers which allowed her to assume the shape of a hawk, while Loki the Trickster was a master shapeshifter, taking such shapes as a hawk, an otter, a salmon, and even a mare. It was in this latter form that Loki became pregnant, giving birth to Sleipnir, the eight-legged steed of Odin.

The Gods of Olympus were often known to punish mortals by transforming them into animals: Hera changed Cal- listo into a bear for having an affair with Zeus, while Athena turned Arachne into a spider after defeating her in a weaving contest. To discover if the guest at his table was truly a God, King Lycaeon served Zeus a meal of human flesh, and the angry deity turned him into a wolf; it is from this particular Greek myth that we acquired the word, lycanthropy. In Western Europe, lycan¬ thropes were wolves or bears, but in other countries, they could assume the forms of other animals: lions and hyenas in Africa, leopards in China, and tigers in India.

Among the Japanese, humans seldom changed into ani¬ mals; rather, animals turned themselves into humans. These shapechangers (hengeyokai) included foxes (kitsune), badgers (tenuki), domestic cats, and huge water-dwelling serpents, the latter of which were known as orochi.

Although no one believes in lycanthropes and shapechangers in this modern age of science and technology, these primal archetypes still remain buried deep within our psyches, and even today we are frightened and fascinated by werewolves and other shapeshifters in story, art, and film.

Perhaps that is the reason why “Furry Fandom” exists: we still believe in the myth of the werewolf, and secretly desire the power to cast aside our problems and our inhibitions with our human shapes.

.. .But is the answer assimple as that? Are an thropomorp hies the animal totems of the 20th century? Or are we simply remembering an earlier age, when the lines separating people and animals were not as clear as they are now?

Here are the answers to “MY MYTHICAL ‘MORPHS”:

1. MERMAIDS

2. MINOTAUR

3. THE UNICORNS

4. THE LOCH NESS MONSTER

5. THE FIRE-BREATHING DRAGON

6. THE YETI